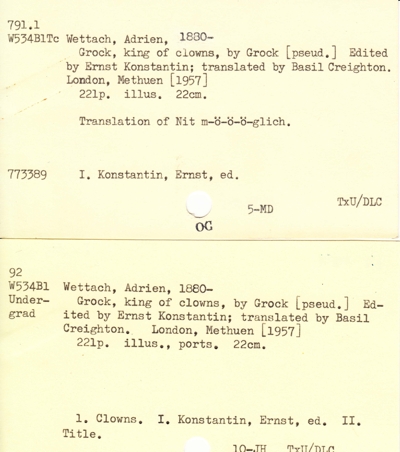

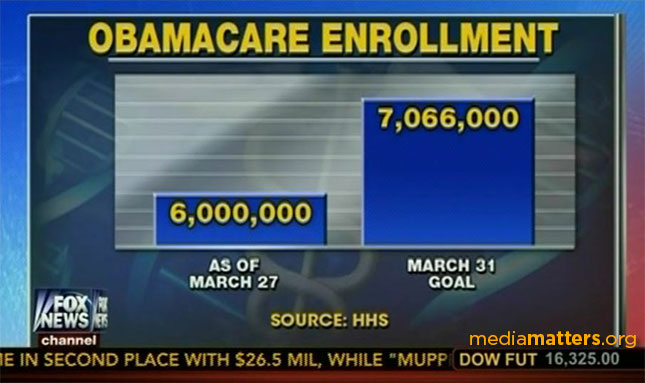

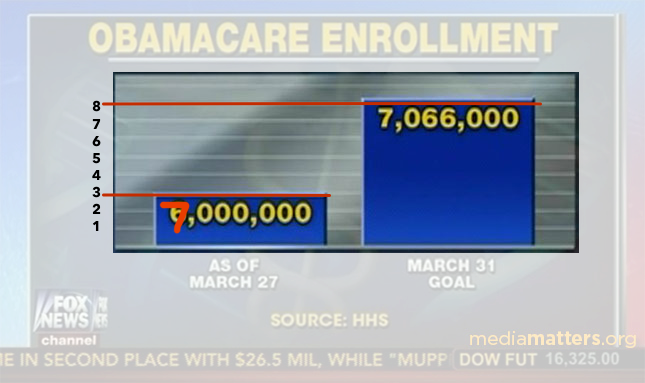

Today is the last day you can sign up for health insurance via the Affordable Care Act exchange. Here’s the chart thrown up by Fox News:

Look at that! LOOK AT IT! Look at how far short “Obamacare” has fallen from its goal! IT’S A TRAIN WRECK! WE TOLD YOU SO! ARGLE-BARGLE!

Argle-bargle indeed.

Let’s pretend we studied propaganda techniques in school and take a look at this chart.

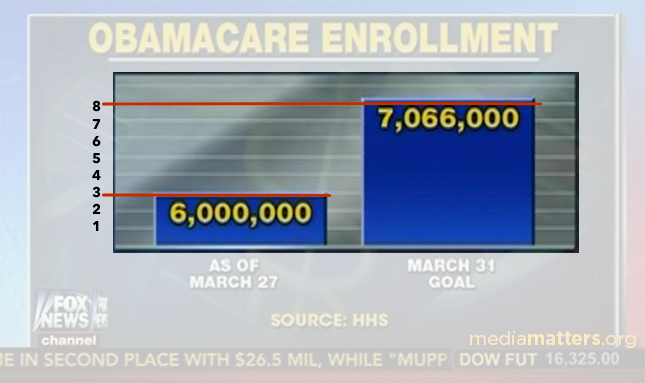

Here we’ve isolated the chart and done some examining of the units of measurement so generously provided by Fox News Corp.

There are eight divisions. I’m lazy, so I’m going to go with the 6,000,000 number since it’s even. It takes up three of the divisions, which means that each division is worth exactly 2,000,000.

So for each line that the bar reaches, that’s another two million people who have signed up for health insurance on the ACA exchanges.

The second bar reaches just past the eighth line, which means that…

Hold on there, bucky, that can’t be right, can it? The second bar reaches past the eighth line, but Fox News Corp. has labeled it 7,066,000.

But if each line is worth 2,000,000…

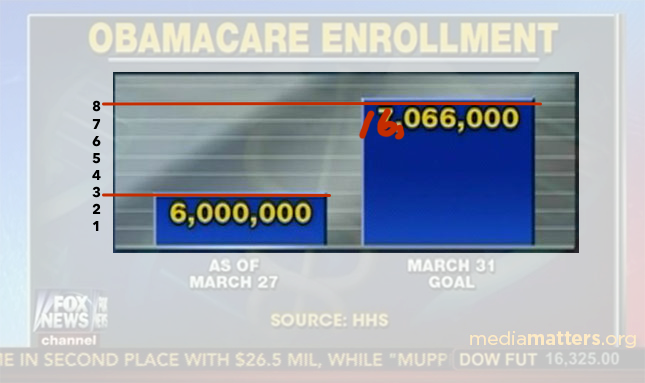

There, I fixed that for you, Fox News Corp.

Here’s what we tell the third graders: always look to see who is giving you information and what they’re trying to sell you. Here we find that Fox News has deliberately distorted the comparison between the 6 million and 7 million columns so that it looks like “Obamacare” has fallen short of its goal by about eleventy-million. (Either that or they are incredibly incompetent. It’s the classic choice of “stupid or evil.”)

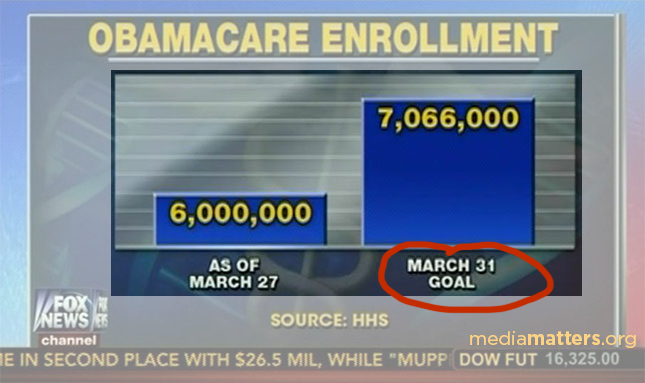

But there’s actually more lying to look at:

We see that as of last Thursday (March 27), the ACA had registered six million people, but that is short of the actual goal of seven million.

However, that’s a lie. The 7,000,000 figure was the Congressional Budget Office’s original estimate of how many people would sign up for insurance via the federal exchange. Because of the website’s bumpy start (sure, private industry contractors can always do a better job…), the CBO revised that estimate downward to 6,000,000. Again, this is not a goal, it’s an estimate.

So here’s the actual news:

Based on the CBO’s revised estimate, the Affordable Care Act goalpost of 6,000,000 people signing up for health insurance on the federal exchange was passed four days before the deadline.

Here’s what Fox News Corp. reported in its chart:

Obamacare has failed to meet its goal of 7,066,000 people by a factor of about 2.66.

Here’s the deal, O conservative acquaintances: we can differ on whether “Obamacare” is a good thing or not—personally, I think it is a waste of time: let’s go straight to single payer universal healthcare. But you cannot pretend that Fox News Corp. has done anything but lie to you with this chart. Not to me, darlings; I don’t watch that particular entertainment channel. To you.

And so what you have to ask yourself is what I would teach third graders to ask: What are they trying to sell you, and why?

Feel free to respond in comments, but we’re only discussing the particulars of this chart. Comments about the ACA and its legitimacy will be deleted. There will be no Gish Galloping here.

(hat tip to Media Matters)

UPDATE

As of midnight last night…

There, I updated that for you, Fox News Corp.