: Ritual identity :

What ritual roles and offices are operative—teacher, master, elder, priest, shaman, diviner, healer, musician? How does the rite transform ordinary appearances and role definitions? Which roles extend beyond the ritual arena, and which are confined to it? … Who initiates, plans, and sustains the rite? Who is excluded by the rite? Who is the audience, and how does it participate? … What feelings do people have while they are performing the rite? After the rite? At what moments are mystical or other kinds of religious experience heightened? Is one expected to have such feelings or experiences? … Does the rite include meditation, possession, psychotropics, or other consciousness-altering elements? … What room is there for eccentricity, deviance, innovation, and personal experiment? … Are masks, costumes, or face paint used as ways of precipitating a transformation of identity?

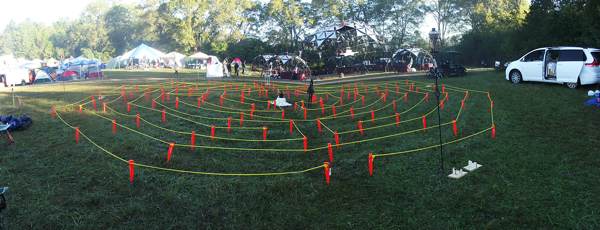

Again, I think there are two rituals going on in our camp: the ritual we perform to become Old Men, and then the ritual experienced by those who walk the labyrinth. I’ll try to keep them straight as I move through this section.

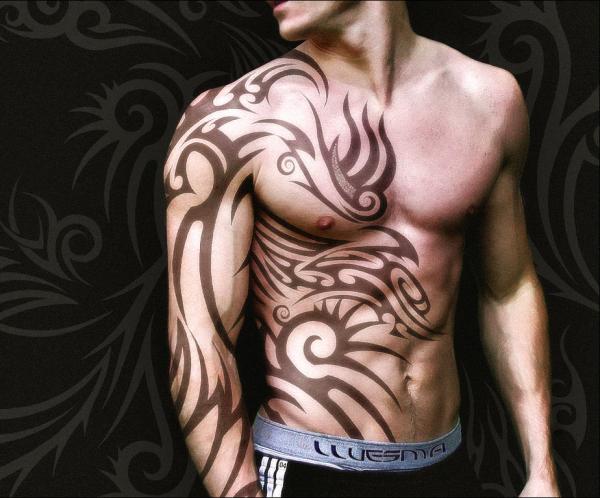

I don’t know how others felt, but I for sure felt as if I were elder, priest, and occasionally a shaman while I was in our ritual. The transformation from Alchemy camper into Old Man never failed to ring true for me. I felt not necessarily exposed, but opening to the onlookers: “This is my body,” if you will. “I mark it, I draw attention to it, I show you the way in, and now I become an Old Man who can assist you. Follow.”

While officiating, I felt very calm—outside time—while at the same time alert to the participants and their choices. I found myself reviewing the original list of traits: solemnity, compassion, serenity, wisdom, openness, and groundedness, and trying to embody and project those to onlookers and participants.

Someone commented that they noticed that I smiled much of the time. Truthfully, it was a conscious decision on my part to return all the positive energy that I was absorbing to the environment. Alchemy and 3 Old Men made me very happy, and I wanted to give that back.

It is interesting that in the original post I was still dithering about the body paint and the nudity. I was fairly sure that it was what we needed, but at that point the troupe was all my theory and no real practice. Needless to say, it was amazing to perform and to watch. I’ll have more thoughts about this element in a couple of days when I talk about ritual action.

I am very curious as to what people’s feelings were when they walked the labyrinth. That’s one thing I want us to do better in the future: collect responses, either through interviews or with some kind of book people could write in.

Was there room for “eccentricity, deviance, innovation, and personal experiment”? You betcha. I think that’s one of the strengths of 3 Old Men, that we opened the labyrinth for others to build their own experiences. It never bothered me to see people romping through it, or stepping over the ropes to be ‘clever’ in ‘finding the way out.’ Everyone brought what they needed and took what they needed.

As I said in the original post:

I expect to see people walking the labyrinth in silence and prayer; singing and dancing; giggling and inattentive; naked; stoned and lost; smirking and cynical; hurriedly. I expect drummers and other musicians to join us. I expect people to be puzzled or put off by the offer of an agon; I expect some to accept it gratefully, with tears, with joy. I expect to be quizzed—”What is this about? How do I do it?” I expect to be ignored. I expect to have others expect me to be something more than I have offered.

And I expect to be transformed by all of it, to learn more about my identity as an Old Man.

And so it was.