See this map?

The red star is where Sue’s cabin is. Sue grew up in Middleport, and so we got in the car and DROVE ALL OVER WESTERN NEW YORK, KENNETH! We had to go pick up our intrepid co-travelers in Oak Orchard, and then we were off.

We went to the cabin that Sue’s parents had when she was a small child, now renovated by a nice lady (Priscilla) whom we met after trespassing into her back yard. (We had thought no one was home.)

The view from one’s seaside yard is simply incredible…

…BUT it’s treacherous. When Sue was a child, there was a road in front of the house. The lake has taken about 30 feet of shore since then, the road with it.

Which makes people like this…

…extremely hard to understand. Sue said, though, that those cabins had been there since she was a child.

Sue insisted that we see the Shoe Tree—entertainment possibilities being limited in western NY—which is out in the middle of nowhere at the intersection of three roads. As it turns out, it’s perfectly charming.

The story is that a while back some teenagers were out one night—entertainment possibilities being limited in western NY—and decided to toss their shoes into the tree. Knowing that the townsfolk would be double-plus unpleased, they convinced all their friends to do the same, there being safety in dilution of culpability. Then they invented the excuse that if you did this, you could make a wish.

Extremely limited.

Western NY is almost entirely agricultural, mostly subsidized corn for ethanol and cattle these days. The large manufacturing plants—GM, Heinz, etc.—are long gone, and with them the comfortable union jobs.

In Middleport, we saw Sue’s childhood home and some other lovely homes, and the Universalist Church, built in 1841:

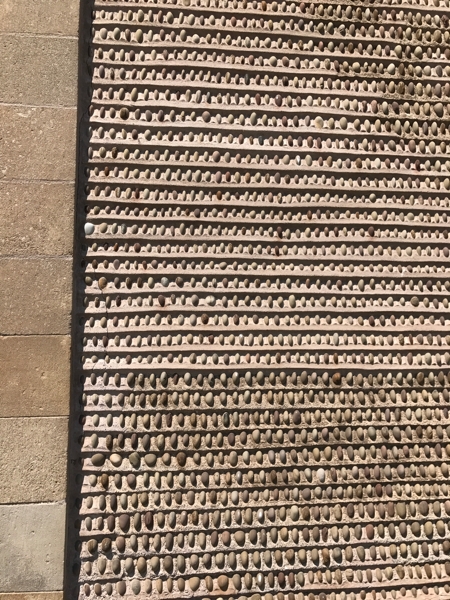

The church is closed, with no one particularly interested in buying it. Here’s the interesting feature:

These are stones brought by the townsfolk from the lake by cart. This surface treatment is in line with my hypothesis that given sufficient materials and time, humans will prefer the ornate.

On to Lockport, which got its name because it sprang up at that point on the Erie Canal with the biggest drop in elevation, requiring five locks in a row (the Flight of Five). We were there to take the Lockport Cave tour.

Right across from the tour center…

Yes, we are organized. Resistance is futile.[1]

Before the tour, we grabbed lunch at Lock 34, a really nice restaurant. Lockport is a sizable little town with arts and stuff going on. We saw a ballet studio, a community theatre in an old movie palace, a general arts place, and there’s a concert on the lock on Friday.

At lunch, I thought it was important that I have a Mule.

Canal and all that.

The Canal is still there, of course, and modernized. You will remember that we became intimately familiar with lock technology from the Danube, and so we were nodding sagely—if not smugly—as our tour guide explained it all to the rest of the group.

This is the new lock. There’s only the one, and it takes about 20 minutes for a boat to get through these days.

Unlike the old locks, when there were five, each taking about an hour plus a three–four day backup of canal traffic each way. Look at these doors (which have been reconstructed):

It took four men on each gate to open and close them, so eight guys per lock. Here’s the other end of the gate:

Mmmm, wood.

A replica of a boat of the period:

Quick view of the Flight of Five:

The tour group walked on down the Canal to the upside-down bridge:

This is the oldest remaining example of this engineering compromise. The story is that during the Civil War, the supply of iron was being fought over by the munitions manufacturers and the railroads, and one of the areas of compromise (presided over by Lincoln) was that all bridges had to be built like this, with the supporting superstructure underneath the railroad instead of above: it took a third less iron to build it this way.

All along the path, our guide pointed out the locations of several factories which had been built on the canal above us: a fire hydrant factory (invented in Lockport by Birdsill Holly), a ceramics factory, and then this:

This is a pulp factory You floated your logs in the channel in the foreground, then fed them into the holes in the wall, where millstones would grind them to pulp. The pulp was pressed into cups and plates and bowls, but those things were not disposables in the 19th century. Families often used them for as long as five years. (Eventually they decided that stainless steel made for more durable and more sanitary tableware.)

The hole on the right was the exit flume for the “cave,” actually a large tunnel carved through the limestone rock to channel water to power the factories above. This was the design and work of B. Holly, who it must be noted had only a third-grade education. Engineering was different in those days.

And here we are entering the cave:

Cast iron tube, still sturdy after 200 years. Steep climb, leveling off to:

This channel was dug by Irish immigrants for about 2¢ a day, plus whiskey. Teams of two would drill a hole in the limestone by hand, pack in a little explosive, light the fuse, then run away. After the explosion, they would carry the debris out the only entrance, way back where we started the tour over the Flight of Five. They did this one basketball-sized amount of limestone at a time. (This is the same limestone used to build buildings in Lockport and Washington, DC.)

When the channel was in operation, the water would have filled the space to within three feet of the ceiling.

One fun fact, which may or may not be true: embedded in the limestone was gypsum, which was worthless to people who wanted the limestone debris for other purposes. The wives of the Irishmen would take it, polish up little bits of it, then schlep it up to Niagara, where they would sell it to tourists as “solidified mist from the Falls, sure,” made by a technique known only to the little Irish ladies of the world. For a dollar—more than their husbands made in two months.

After the cave tour, which included a boat ride, we went to the Flight of Five Winery and we had a tasting.

All very tasty. We bought one or two. Or three.

Our final stop for the day: The Culvert.

And what is this, I hear you ask? It is the only place where a road goes under the Erie Canal. The Canal goes through a valley here and is actually contained in berms. It made more sense to take the road under it than to build a bridge over it. The road was actually closed to traffic because they’re making repairs right on the other side, but we scoffed at their attempts to keep us safe.

—————

Lovely! Sorry to see you go.. Elpie says it is waaaaay tooooooo boring here suddenly without his uncle dale and aunt Ginny. And has taken to the deck to sigh it off.. maybe … maybe he says .. it’s a mistake and you will pull in n a minute and he can get going again

. Good to see you! Thanks for being here

Ok I give up.. WHO IS KENNETH!

Remember when Dan Rather was accosted by the crazy guy on the street? The crazy guy was shouting, “What’s the frequency, Kenneth?” and it actually became a rock song. It’s kind of a wild-eyed, ranty kind of screaming comment.

Elpie has taken up residence in his uncle dail’s bed holding out hope!!

I have just reviewed the western NYs posts of your journey and , definitely Dale, you should be hired by the area to beckon all ” foreigners” ( I.e. Anyone NOT from Western NY— and YES, it IS “western NY, NOT “UpstateNY”).. great job, Dale

Thanks—we had a great time there!