As I work my way through the text of my putative book on the creative process, you might like to read the rest of the text so far here. Also, the rest of my meditations on the process here.

Chapter Two: Framework

The most perfect ape cannot draw an ape; only man can do that; but, likewise, only man regards the ability to do this as a sign of superiority. GCL, J.115

—————

Before we begin looking at the Nine Precepts, I want to lay out some basic ideas about creativity that are critical to the way Lichtenbergianism works.

We are all creative. Every one of us. It is inborn in us as humans. As I say in my Arts Speech[1], every child on this planet sings, dances, draws, and pretends long before she learns her ABCs or can count to 10. This is true of you, even if you think it’s not.[2]

However, most of us don’t see ourselves as having the ability to create because we are cursed to live in an amazing world. We have at our fingertips perfect performances of perfect pieces of music, perfect paintings or sculptures, perfect novels, even perfect photographs of perfect gardens—and we have allowed ourselves to believe that this perfection is the natural product of creativity.

It seems clear to us that only creative geniuses can produce such a level of perfection. Mozart is the supreme exemplar of that kind of creative genius, and I think it’s important to embrace this truth: mere humans can’t do it.[3]

However, it’s also important to embrace this as well: creativity is not genius. We all want to be creative, and we all can create.

So what is creativity, then?

MAKE THE THING THAT IS NOT.

It’s that simple.[4]

That’s art. Where there was not a thing, now there is. A poem, a musical work, a painting, a sketch.

A dance, an algorithm, a solution, a book, a lesson, an exhibit, an article, a movie, a manifesto.

A drumming, a journal, a cocktail, a script, a mosaic, a website, a children’s story, a documentary, a photograph.

It’s all out there—except it’s not, of course. It’s out there, but not until we find it and drag it—often kicking and screaming—into our version of reality.

How do we do that? Or rather, more to the purpose of this book, how can we make it possible for us to do that?[5]

Many years ago I encountered a very early version of an e-zine, created in Apple’s late, lamented HyperCard. I think it was called “The Bad Penny.” Its focus was on publishing work from people anywhere and everywhere, to give them an Audience. In its first issue, the editors wrote a manifesto that contained a key idea that has stuck with me: what the world needs is more bad poetry. Create with abandon. Create more and more poetry. Make it happen—flood the world with it. Don’t worry whether it’s good or not, just write it.

The point was to encourage people to create, and that’s the purpose of Lichtenbergianism.

But, you will object, I’m not really an artist. I buy those adult coloring books, but I can’t really create something new. I enjoy my Friday night sessions at the Sip ‘n’ Paint studio, but I can’t really paint a real painting. I scribble notes in my journal, but I’m not a real poet.

Right. So what do you call a person who paints or writes poetry or composes a song?[6]

Before we even begin, we must beware the “impostor syndrome,” that still small voice in the back of our head constantly warning us that sooner or later all the Others will discover that we are not who we are pretending to be. “They” will take a good look at our work, realize that we are a fraud, and they’ll set up a hue and a cry to alert the others. (Don’t you have the image in your head of Donald Sutherland raising the alarm at the end of The Body-Snatchers? You do now.) Really, we all feel this way. I feel this way.

I cringe every time I post a new piece of music on my blog or refer to myself as a composer—or when I started posting bits of this book online and pretended to be an author—because I’m not really.

Pfft, is my advice to you (and to myself.) There are so many ways to put this: Assume a virtue if you have it not. Fake it till you make it. Just do it.

Just Make the Thing That Is Not.

Tomorrow: the rest of the chapter

—————

[1] cf. The Arts Speech, Appendix B

[2] Of course you think it’s true. You wouldn’t be reading this book if you didn’t think it was true.

[3] (Professor Peter Schickele reminds us that this is why the completely incompetent P.D.Q. Bach is such a comfort to us: after encountering Mozart, we feel like inadequate parasites; after encountering dear P.D.Q., we feel as if perhaps we could do as well if not better.)

[4] Ha. As if.

[5] (Creativity is not limited to artists, of course; I will use the word artist to include and connote painters, designers, actors, composers, writers, scientists, programmers, teachers—et al.)

[6] Answer key: a painter, a poet, and a composer. If Margaret Keane, Rod McKuen, and Coldplay have earned the title, so have you.

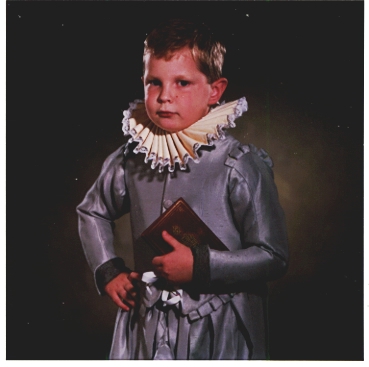

Story #4: All right, I have four more favorite stories. My son Grayson played Prince Mamillius. He was seven at the time, and I needed a Mamillius who could read and whose television privileges I could threaten. My mother volunteered to sew his costume, but she balked at putting on the codpiece—so that night at dress rehearsal I’m safety-pinning a codpiece onto my child when he objects. “What is this?” I explained it was called a codpiece. “What’s it for?” I explained its origins as a “safety valve” from tight leggings in the late Middle Ages, but that at this time period it was merely decorative. “Do the other actors who are male have one too?” (That is literally what he said.) Yes, I said, they all do. He considered for a moment, then announced, “I can use this in my scene: ‘No, my lord, I’ll fight!’” and waved his little codpiece about. I proposed that that might be funnier to spring on his fellow cast members backstage rather than as a bit of onstage business.

Story #4: All right, I have four more favorite stories. My son Grayson played Prince Mamillius. He was seven at the time, and I needed a Mamillius who could read and whose television privileges I could threaten. My mother volunteered to sew his costume, but she balked at putting on the codpiece—so that night at dress rehearsal I’m safety-pinning a codpiece onto my child when he objects. “What is this?” I explained it was called a codpiece. “What’s it for?” I explained its origins as a “safety valve” from tight leggings in the late Middle Ages, but that at this time period it was merely decorative. “Do the other actors who are male have one too?” (That is literally what he said.) Yes, I said, they all do. He considered for a moment, then announced, “I can use this in my scene: ‘No, my lord, I’ll fight!’” and waved his little codpiece about. I proposed that that might be funnier to spring on his fellow cast members backstage rather than as a bit of onstage business.