More fun in international emailing.

In addition to trying Frances Hollingdale’s email—which may or may not be current—I have emailed the permissions department at Penguin Books. (Note to Penguin: it took me five minutes of clicking through to find anything like a contact email. Giving us the Underground stops near your three London offices and what the neighborhood used to be like and what it’s like now is… shall we call it quaint instead of twee? Sure. I’ll be sure to stop by when I’m on my book tour.)

But there’s more.

Way back in the 70s, I stumbled across an article somewhere about the Danish mathematician Piet Hein.[1] It focused on his winning a design contest for a traffic roundabout by using a curve that he called a superellipse. I seem to recall that the article claimed he “invented” the shape, but that is not the case.

The article also mentioned that Hein was a poet, whipping out these aphoristic little poems he called “grooks.” I do not remember whether this one was in the article; I don’t remember where I came across it. But it struck me very deeply, to the extent that I memorized it instantly and it has remained one of three poems that I’m sure I will be able to recite flawlessly in the Home.[2]

At the risk of jeopardizing my standing in requesting permission to include this text in Lichtenbergianism, here it is:

TWIN MYSTERY

To many people artists seem

undisciplined and lawless.

Such laziness, with such great gifts,

seems little short of crime.

One mystery is how they make

the things they make so flawless;

another, what they’re doing with

their energy and time.

(To make up for this transgression, I offer links to go buy all of Piet Hein’s Grooks. Ironically, when I searched online to see if there were an official site I could link to for the poem, one of Google’s offerings was me, in the SHAKESPER listserv way back in 2001, when as a part of some long-forgotten discussion I posted it, targeting Terence Hawkes for some reason.)

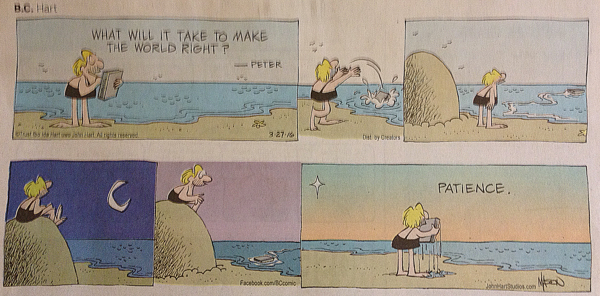

Obviously I would like to include this little gem as a sidebar in the chapter on TASK AVOIDANCE, currently under revision. The official Hein website warns me that there will be a fee involved. We’ll see if it’s worth it.

While we’re waiting, go check out the Hein website. Click on the Games & Books section. I like the Super-Egg, the three-dimensional version of the superellipse. Be advised: they’re only 1-1/4″ tall, which for the price (plus shipping) is something I’ll have to buy with my lottery winnings.

But also notice the Soma toy. I had completely forgotten that Hein was the inventor of that one! I had one, in blue plastic, and it survived long into my adult years. In fact, it may still be up here in the study somewhere, just buried under the archaeological layers.

At any rate, we have more for our waiting game.

—————

[1] Maybe Martin Gardner’s reprint of his article in Scientific American, Sep 1965, in Mathematical Carnival, 1977, although that seems late for me to have encountered it. I thought I remembered the grooks in college; I am very probably wrong.

[2] The other two are “Jabberwocky” and “Sonnet 18.”

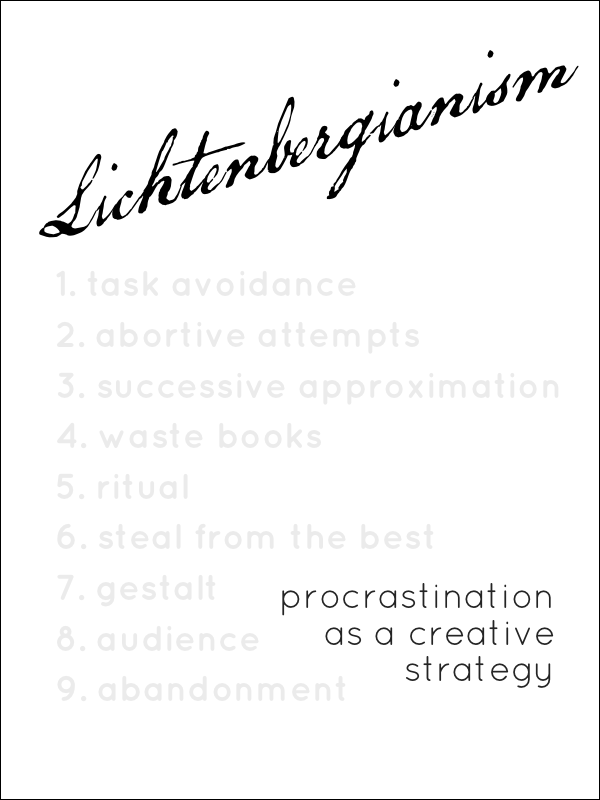

Likewise, there is no shortage of books which will help you deal with your tendency to procrastinate. Why, just yesterday I was contacted by a writer who is writing his own meditation on the subject and who felt compelled to get in touch with the Chair of the Lichtenbergian Society in order to find out more about us—just as I was editing the chapter on TASK AVOIDANCE.

Likewise, there is no shortage of books which will help you deal with your tendency to procrastinate. Why, just yesterday I was contacted by a writer who is writing his own meditation on the subject and who felt compelled to get in touch with the Chair of the Lichtenbergian Society in order to find out more about us—just as I was editing the chapter on TASK AVOIDANCE.