I haven’t blogged about seeing Alice in Wonderland, the new opera by Unsuk Chin at the Bayerische Staatsoper.

This is Ms. Chin’s first opera, and it premiered at the Munich Summer Festival this year. In other words, this is a really new work, and you know how I am, searching for new stuff that works.

Let me restate that. I am constantly examining new music, especially new opera, in the hopes that contemporary composers can speak to me (and presumably other audience members) in ways that composers of the past have. As I type this, for example, that old reprobate Wagner’s “Liebestod” from Tristan und Isolde is playing on iTunes. Even given the march of progress in tonality and all that jazz, can a new work elicit that kind of eyeballs-rolling-back-in-the-head response?

Generally not, is my finding so far.

My response to Alice has a lot of tangled threads, involving the nature of creativity (vid. sub.); the purpose of opera; and William Blake’s Inn, both music and stage version. So bear with me if I don’t get them all separated.

First, the music. Ms. Chin studied with Ligeti, and it shows. She allowed herself a little leeway in the melody department, but not much. Every other piece dissolved into polyphonic cacophony; once you’ve heard all four percussionists banging on everything in the room, you’ve heard it. Adding a few more trombones does not change the essence of the experience.

However, I think her score was generally solid. There were a couple of lovely moments in it, and more than several witty ones. (I think I caught a Mahler joke when the Mad Hatter was singing “forever” on the same notes that end Das Lied von der Erde.) I might even have liked it a lot if the staging hadn’t killed it, about which see more later.

The book was by David Henry Hwang, and it was not bad at all. (The opera was, amusingly, in English; I found myself reading the German subtitles more than half the time.) It follows the general outline of the book; some of the arias swerve off into some really nice surreal lyrics. Again, the design of the production completely undercut the actual libretto (which is in the souvenir program I bought). I’ll discuss the beginning and ending later.

Alice’s design looked, from the Staatsoper’s website, to be cutting edge European, so that was part of its appeal when I booked the tickets.

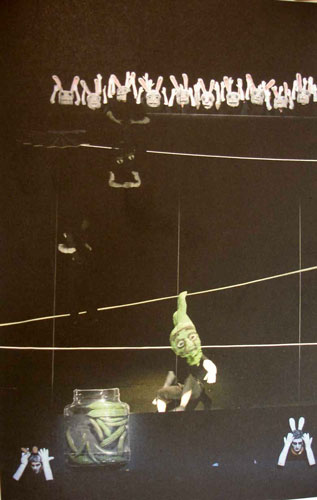

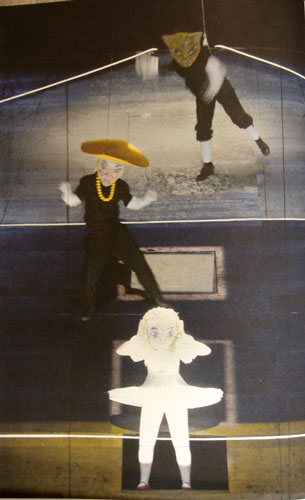

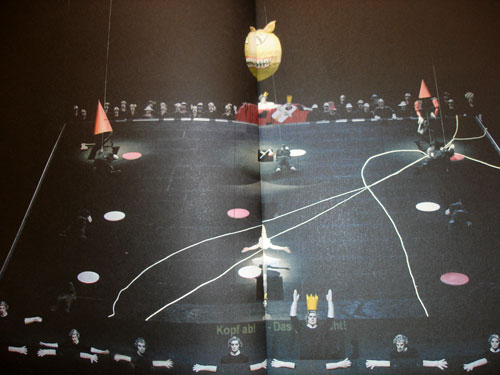

Behold:

But in fact the design killed the entire show. Look at the last one above. That huge raked stage was permanent. It was at a 45° rake the entire evening, which means that the nine performers (not singers) who popped out of the nine holes had to be tethered with wires the entire time. And that meant that they were more or less stationary puppeteers the entire show. Alice herself never moved from her down center hole. [Note to Marc: Shut up.]

The disembodied heads you see at the bottom of the set in their own separate trench are the excellent cast of seven. Those are not their arms/hands in front them. They are puppet arms, manipulated in unison usually by the cast.

Check out the third photo. That’s the Duchess and the first of many Cheshire Cat avatars. They are sung by the disembodied heads down front and pantomimed by the tethered performers. In place. If you’re thinking that this might get to be boring, you’d be right, especially since no one onstage ever had a face; they were all masked or puppeted. In fact, in one number, top of the second half (billed as an opera in one act, it nonetheless had an intermission halfway through), the puppets shook their heads once, then didn’t move for the rest of the scene. Oh. My. God.

That last photo also shows the chorus, in their separate trench at the top of the set. File on, file off. The children’s chorus appears at the top of the second photo. I don’t remember what significance the giant jar of pickles had, if any.

Static, static, static. I was especially appalled by this elaborate oratorio approach after intermission, during which I read Hwang’s libretto and found that he and the composer had called for a rambunctious staging. How do you get from the Tea Party scene and the Croquet scene to an immobile cast of puppets?

So let’s see if I can enumerate my issues.

The purpose of opera. As you may know, the old argument is “words or music,” which is more important? Richard Strauss even wrote an opera (Capriccio) to debate the issue, albeit comically. Of course, the debate ignores that there is another layer for the audience to contend with, and that’s the production itself. (Remember, especially for Mozart and fellows, there was no such thing as the disembodied opera of CDs or radio.) I have an Alexandrian solution to this Gordian Knot: theatre is most important. If it’s not viable theatre, then neither the words or the music are going to have the impact their creators hoped for.

In this case, while the music and the words might have provided a springboard for something entertaining and/or provocative, they were stopped cold by the designers and director’s choices. I was reminded repeatedly throughout the evening that our ragtag Lacuna workshop worked more magic with our cardboard-and-hot-glue version of “Man in the Marmalade Hat Arrives” or “Two Sunflowers” than what I was seeing on an international stage. I kept thinking that our methods and our goals breathed more life into our text than did the Staatsoper’s; Lyles and Willard were a lot luckier than Chin and Hwang.

Of course, Chin and Hwang themselves were the source of the bizarre opening and closing, two non-Carollian “dream” sequences. (Hello, the whole thing was a dream, remember?) The opening involved a boy dragging a mummified cat, singing, “It is my fate.” Honey, please.

The ending was worse: Alice was singing a plaintive “What kind of garden has no flowers?”, and the two old men (“twins,” according to the libretto) from the opening returned and commanded her to plant a garden. After some odd and pointless repetition, suddenly hundreds of balls/seeds/testicles? avalanched down the stage. (Previously, at the climax of the “Off with her head” sequence, there was an avalanche of heads. One stopped rolling about a third of the way down, and there it remained for the rest of the opera; no one could reach it to kick it into one of the manholes. A lesson for us all, I’m sure.) There was some “burgeoning” music, the stage floor was lit with colored dots, just as the stage floor had been lit with brightly colored lights throughout, so it was not an efflorescence of any kind, Alice pantomimed “wonder,” and it was over.

What?? Since when was Alice’s story an Amfortas’ wound myth? It was lame and ineffective.

I was very frustrated by the experience: Lacuna couldn’t find backing for William Blake’s Inn, and so it’s a dead issue for Newnan. Yet our vision for the piece far exceeded the Bavarian State Opera’s both in terms of creativity and effectiveness. I realize that’s a personal issue, but I get angry when an organization has the resources to do something really fabulous, something beyond what I could accomplish myself, and they don’t.

And no, they’re not allowed. I pay them to show me something that works, artistically, and they didn’t. If they were NTC or Lacuna, fine. I’ll take my chances and failure is OK. But at the professional level, and such an exalted level as this, I expect success.

Did the place at least have a bar? I’d have to think some Jagermeister would have helped, given your description of things.

Have we worked through all the forms? Are we waiting for a new form to emerge? Should we go back to dancing around the fires and start anew, and see what magic emerges this go-round?

This is one thing that draws me to Southeastern Native American myth, ritual, and song. It has not yet been fully extrapolated. Not even close.

Peter Brook had actors dancing around fires in the late sixties and early seventies. Starting anew. Pursuing myth. Creating myth. He probably also got to sleep with Helen Mirren. You can do anything when the Shah of Iran signs the check, I guess.

I spent a good bit of time before, during, and after grad school chasing a desire that was the epitome of bad faith. I wanted to make theatre that existed primarily as provocative documentation materials. In other words, I wanted to be responsible for some of those compelling photos and descriptions adorning the pages of TDR. That’s what struck me first as I looked at the photos of this production. Good photos. “Interesting” in that subsidized German sort of way. But as Dale attests, dead as theatre.

I do think there is a way to bring the “new” into theatre art or into musical theatre art, and I am unapologetically “Modernist” in that respect (retro, I suppose), but letting “interesting” artists who are not thinking as theatre artists gallop about un-checked is not it. Stuff has to play, you know. Egos have to take a back seat. It’s a most idealistic pragmatism at work in the theatre when things are really effective (Molly, these days, is quite taken with oxymorons; had to throw one in). But mostly the stage is now a runway and theatre is now about watching “interesting” artists walk and turn and pose. I don’t want to see a fashion show when I’m expecting something else…

I don’t think the old forms are dead yet. I hope to explore that issue after the holidays as I buckle down to working on the symphony. I’m here to tell you that it will be tonal and overwhelmingly formal. You will not hear great grinding towers of brass chords full of seconds. And what’s worse, it will be in G major.

I feel like an outlaw.

I agree that the old forms haven’t quite died completely. When I teach comedy writing I play a game with the students. The rules of the game are 1) You have to cheat. 2a) You can’t get caught and 2b) You can’t be a jerk. A metaphor for how I write. Any art–painting, story-tellyng, symphony, et al–will invariable be based on something that has come before it. The trick is to either do it in such a way that no one can really tell or to openly embrace its parallels to its precursor (I submit Moonlight.) Having studied, and based most of my beliefs in art, on the works of Joseph Cambell, whenever I see a work of art, I immediately look for its influences from previous works, and they are inevitably found. Incidentally, I began this practice when I saw Titanic, which everyone at the time thought was one of the greatest love stories ever. I told people to watch Anything Goes. Aside from the facts that one is a musical and one is one is not and one is comic and the other tragic, they are the exact same story. Of course, I am one of those spoil sports that assumes all art is derivative.

Also, Dale, since you only pre-empted Marc, can I comment on Alice’s down center hole?

I love that formula for writing comedy. It’s like the agenda for any character in a good farce. I like thinking about the creative act as essentially farcical.

Regarding brass and minor seconds. This occurred to me the other day as I was listening to a contemporary piece being played on Performance Today (of all things). There is a characteristic either of the age we live in or of the age of certain artists (young, mostly), and I would call it a wish to push to the sublime. Speaking in terms of the Ding en sich (if I may carry our chat on the lacunagroup blog over to here for a moment), the artists I’m speaking of want to actually make “the Thing.” They believe it is a step forward to try for a frontal assault on sense and sensibility, that it is more true, more cutting edge, more vital. They actually believe they can fabricate an encounter with the most impossible-to-realize aspects of intimate human experience.

It’s art as impatience. There is a fine value in crafting something which might be quite humble or quite formally conscious or “traditional” and prods our contemplation toward certain extremes or moves our feelings toward what may start to touch the sublime, and which is content to stay with a modest thingness (small t) in its execution. Satie said music should be like furniture.

I still love Ernst Krenek’s introduction to “atonal” techniques, because it emphasizes the resulting music as the next exploration of poliphony, of the movement of voices, staying in accord with the joyous tradition of Western writing. We lean into the minor second as a new possibility within a long journey of exploration, rather than seizing it as an exposed loop of intestine waiting to be pulled.

Believe it or not, I think the most exciting venues for the continuing development of Western forms is going to be …

are you ready for this?

…video games.

Well, not quite. Not exactly. But, yeah, kinda. With stuff like “Second Life,” we are creating a new virtual public space. Cross that with blogs like these, increased interactivity, more sophisticated music and graphics and themes, new forms of interaction that involve movement (like what the Wii is doing) … We’re a decade or so away, but I personally believe that a form of video game is the “new frontier” for the Western art forms to spin off and do their thing. So, you’re right … it ain’t dead yet.

But the symphonic form, particularly? You’ll have to do some convincing there. Isn’t it reaching its end? Hasn’t it run through all its significant forms? Isn’t it true that all we can do now is ape what has gone before or make noise?

As for theatre and film, I think there are still some rooms left to explore. But where do we go after Shakespeare (and especially after Beckett)?

Discuss.

All of the discussion in our culture about how the [fill-in-the-art-form] is reaching the end of its existence presumes a linear progression, a birth-apogee-death arc that has little to do with actual art.

I reject that presumption and reject the 19th century idea of Progress. If I write a formal symphony in G major, then anyone who can’t hear it without using the ears of mid-20th century academia is not really listening to it. They are no better than Stalinist apparatchiks.

Is this a manifesto?

Have to disagree with you there. If territory has been thoroughly explored, it’s dead territory (for the artist), IMHO. Unless you’re gonna sample it, mix it up, put it into a blender, and make some kind of collage.

Not to say all progression is linear. But the word is PROGRESSION.

And that’s what I reject, the very concept of PROGRESSION. B springs from, or derives from, or rejects A, and therefore we can never go back to A. We must PROGRESS.

Hogwash and fiddle-faddle. It smacks of triumphalism, exceptionalism, and Social Darwinism.

The sonnet is still viable; tonality never lost its centrality; the sonata form still elucidates. Shostakovich wrote his own set of 48 preludes and fugues, and damn fine ones they are, too.

The problem in music is that our most talented composers have for three generations been sternly warned away from the “old” stuff. Anyone who wrote a melody was ridiculed. And so now, no one who would be any good at it knows how. When only hacks are allowed to write “pretty” music, you get only hackery.

I think I’ve written before about how shocked everyone was that Paul Moravec’s Tempest Fantasy won the Pulitzer in 2004 because it was “so sunny.” Trust me, it’s not even close, but apparently it was scandalously recherche to the majority of the classical music establishment.

The situation is no different than Charles Ives’s composition professor (Horatio Parker, wasn’t it?) forcing him to end his Symphony No. 1 in the same key it began. Tyranny of the academy, pure and simple.

As for the symphonic form being “dead,” how can you tell? No one’s been allowed to write a real one in years. (Not purely true, but you know what I mean.)

I think we have let ourselves get wrapped up in the seductive strains of…you know me…a discourse. Whether we want to resist or not, we are influenced by cultural criticism, art criticism, trend-spotting. Basically a high-level middle school club fair, I think. I hear the French club takes the best trips. Everybody’s signing up for FBLA (not, of course, but you get the idea). Computer club’s really where it’s at.

I think to debate this you have to make some assertions about the nature of art. And accept that our investment in our position has everything to do with our own personal priorities, dispositions, appetites, what have you. There are those who strive to make their interests coincide with what seems to be on the horizon in the Zeitgeist and are very good at always seeming to ride the most forward wave. Harold Bloom asserts that all artists struggle with the sense of belatedness as they look back and try to look forward. Lines and circles imply two distinct temperaments seeking solutions.

Fact of life. Something is always going to be capturing people’s enthusiasms. Do you wish to excell at the art of capturing people’s enthusiasms? To an extent I say, again, it’s temperament. For instance, I’m a naturally pessimistic kind of guy who approaches questions of fashion very much like a fox with the grapes. Knowing I’m never going to lead anybody into a brave new world, I retreat into esoteric pursuits and hope it sends out ripples. I can’t conceive of harnessing the gaze or ears of multitudes. My attitudes on the purpose of art run accordingly. And my thinking about its future.

I’m wondering if this debate is working with two approaches to creation. In one, the progress of technology and sensation control is bringing the artist closer and closer to being able to duplicate “reality,” to fashion a created “experience” that can compete with everyday experience by privileging “likeness” as the supreme value. Art strives to create the semblant. The other view lies more toward the artist as a creator of meanings, of fashioning new symbolic systems for understanding reality or teasing out new aspects of reality. Forms and structures in themselves give us everything we need. Symbol and substitution are at play. Art is not simulating a universe; it is adding to the things in it. I think there are better ways to draw the distinction. I’m improvising.

What marc said.

Jeff, that was the weakest S2 I’ve seen to date. 🙂

Unless it was an S(/), in which case I take it back.

And that’s a problem with you Lacanians: observe and dissect the discourse, but mercy, let’s not get wrapped up in it. Quel passé.

Except, um…

I don’t really think that’s the distinction being made.

I’m not advocating a Xeroxing of the Universe. Not at all. What good is 1-to-1? I guess it’s good for scientific simulations, engineers, etc. Good for building models and projections. But that’s not art.

What I’m saying is … the Dragon don’t read Shakespeare.

He don’t listen to Bach, neither.

The Dragon consumes them, digests them, excretes them.

We poke at the ashy remnants — oracles with entrails — looking for “meanings.” The Dragon laughs at us and takes flight. He’s hungry again.

Our choices are two:

1. Powerful metaphors. FIRE. (What never was, on land or sea.)

2. Endless description. ICE. (The hopeless but wholly practical quest to capture and crystalize WHAT IS.)

Take your pick. How you pick defines who you are.

I’m going to go out on a very passé limb here. Yes, I agree with what’s-her-name, Dissanayake, that the arts evolved to bring people together. Yes, I’ll take Marc’s proposition that artists can seek to appeal to people’s enthusiasms. That would be the “bringing together” part. Yes, I think I can create meaning in a disregarded form, i.e., the symphony, and generate enthusiasm in its listeners through the outmoded vehicles of melody, harmony, repetition and variation, tension and release, and form. And I’m betting that no one who consciously avoids those outmoded vehicles can make much headway in the other goals. You may please the academicians without melody and form, but only because you’ve presented them with a deliciously thorny problem that they (and only they) know how to solve. It is an exclusive club, the Academy, and one whose enthusiasm I do not hope to engage.

Wow. I must have struck a nerve. I’m a ‘Triumphalist!’ An ‘Exceptionalist!’ A ‘Social Darwinist!’ Them’s fightin’ words! I’m even trying to gain membership to the Academy! Groucho would be incensed. You’d smell him coming. Of course you would, he’s dead. He’s senseless. He CAN’T be incensed! They didn’t even cremate him, so the point is moot. Unless he were talking, which he can’t, because he’s dead. If he WERE alive, you know what I’d say? Now THAT’S Triumphalism! Joyful triumphalism. How appropriate, given that it’s the holiday season. I mean the given season. Have you given? If you’re a-givin’, I’m receivin’. But, please, no incense. My wife’s allergic. Only on Sundays, though. I haven’t quite figured that out. Go figure. No, not you. You’re no engineer, you’re no good at mathematics. What did they teach you at school, anyhow? Evolution?

So which is Beethoven’s 6th, “Pastoral,” FIRE or ICE?

And, hello? You delimit our choices as if there’s some great pity that we no longer have other options or something. But what other options were there ever than revolution or recapitulation? I’m not understanding the hysterical/antihistorical tone of the Dragon bit.

No, I don’t spend time bemoaning coulda, woulda, shoulda.

And, of course, my dualistic 1 or 2 is just another metaphor.

My “tone” is just my costume. I’ll tire of it soon.

And, lastly, to begin again … hello!

Oh, let’s not bicker about who killed whom or whose epistemology sucks. Let’s just look up the dirty words in the 1736 Canting Dictionary.

You autem-prickears, you.

Leave the ol’ lanspresado alone, mate.

I’l agree that the arts evolved to bring people together (Dionysus would approve). But also, I suppose, to separate … to “ration.” (Apollo gets his due). Your tribe’s arts and rituals ain’t like ours. You ain’t from around here, are ya? The ol’ Us and Them. Who’s in, who’s out; who participates, who doesn’t. And what Magisterium guards the Secret Gnosis? And why am I not a member? What did Mark Twain once say?

Get on the raft, Huck honey?

You guys are entirely too high-brow for me. Inserting my comments in the discourse always makes me feel like the purveyor of audible flatulence in the Louvre’. Just the same, I chatter away.

Despite my inadequacies to follow the exchange of hard-to-pronounce-and-obscure-philosopher-name-dropping and even more obscure shorthand (S?>/, anyone?), I thought this quote was pretty interesting in light of the exchange about tonality/atonality/major/minor/etc.:

To do just the opposite is also a form of imitation.

Georg Christoph Lichtenberg (1742 – 1799)

…whoever he is.

To occupy the position of the analyst is to attempt to hold the place of the “a.” That’s why I claim full responsibility for all the interesting exchanges after 11.

Yeah, I think my distinction in part was my wanting to rib JB for being a virtual lifer. And for valorizing “experience.”

It takes art to create the allegory of the Dragon. It takes art to create the linguistic dislocations in the now classic “entry 18.” Fire AND Ice?

I am wrapped up in it. It’s very compelling. I’ve made popcorn. I’m hoping for more dirty words, though.

I’m still waiting for an answer for #19, or is it a koan? I’d like to think I’ve posed a koan.

You mean this guy?

Actually, he sounds like one of us:

When I first heard the Pastoral, one hand clapped.

And I LOVE flatulence, by the way. Especially when it comes in the form of quotes like that one.

Et voilá! More dirty words.

I was going to do this over at Lacuna but I thought more people probably read this blog so I decided to post it here, instead.

This is a challenge. I am going to put up $25 for ACE, which really needs the money this year. Anyone care to match? We could pool all the money together and donate it in one check and say it’s “From DaleLyles.com” or from from Lacuna or whatever.

Just a thought. Anyone interested?

If everyone matched, we’d have at least 100 bucks to give.

I can do that.

I’m also offering my son as a volunteer (really).

What do you mean more people probably read this blog?

Hey, my uncle has a barn!

At “Dale Says” there’s no such thing as an inadequate insertion. At least that’s what Dale says.

My tooth hurts.

OK, I’ll match your son and raise it a daughter. Although I’m not sure my three-year-old will be of much help. But my daughter has a car and I’m sure she’d be willing.

I refuse to rise to Marc’s calumny.

::sigh::

So here’s the assignment:

Write “no more than a few pages” of the Tom Jones-like novel you’ve always hoped to write.

Due by Saturday.

OK, I’m in.

Of course, there’s still the buttocks thing to finish…

And no, Marc, you may not do Tristram Shandy instead. We’ll do that another time.

I thought these two blogs amounted to our version of Shandy. I guess I was mistaken.

I’m springing from the buttocks thing, myself.

Jesus! Now we have homework?!

No, no, not homework, just a mere soupçon of a challenge. If you’re up to it, of course. I’m about halfway through mine.

I’m moving the Tom Jones discussion to a new post.

Otherwise, carry on.