As I work my way through the text of my putative book on the creative process, you might like to read the rest of the text so far here. Also, the rest of my meditations on the process here.

There are many ways to manage TASK AVOIDANCE.

xxx <— this is my place holder for “needs more cowbell,” in this case some examples of structured procrastination before I get to kanban. (You can leave your system in comments if you’d like me to include it!)

My favorite way of making sure that my TASK AVOIDANCE is productive (and not just laziness) is the Japanese system known as kanban.

Kanban was originally developed at Toyota as an inventory control system and has been adapted for use in other areas, such as software design. Jim Benson and Tonianne Demaria Barry have developed a “personal kanban,” and I highly recommend their website (personalkanban.com) and their accompanying book.

Kanban involves writing down your tasks and subtasks on cards or sticky notes, then subdividing them into workflow stages such as Ready, Doing, and Done. (Benson/Barry emphasize that the system is ultimately adaptable to your workflow, terminology, and needs.)

This first key concept is called “visualizing your workflow,” and the first time you do a kanban dump it’s scary: all those sticky notes with all those things to do! But take a deep breath and remember: you’re going to procrastinate on most of this. You’re just getting organized about it.

The second key concept is “limit your work-in-progress.” Decide on how many of the sticky notes you’re going to actually work on at a time. The usual number is three, certainly no more than five.

As you complete a task, move the sticky note over to the Done column.

That’s all there is to it. (Of course there’s more to it, but that’s it for the basics.)

As Benson/Barry describe the process, the rest of the value of kanban manifests itself through these two key concepts. You’ll begin to get an idea of the tasks you’re avoiding and why. You’ll begin to examine your work practices as you watch the flow of sticky notes.[1] You’ll begin to adapt the system to your needs.

There are a lot of ways to implement a kanban. The easiest way is simply to take a white board and stick sticky notes on it. (The important thing to remember is that your kanban has to be where you can see it as you work.)

There are of course software versions, including free add-on apps for Google Drive.

For a while, I used my laptop, creating a desktop image and using Apple’s Notes app to create sticky notes there.

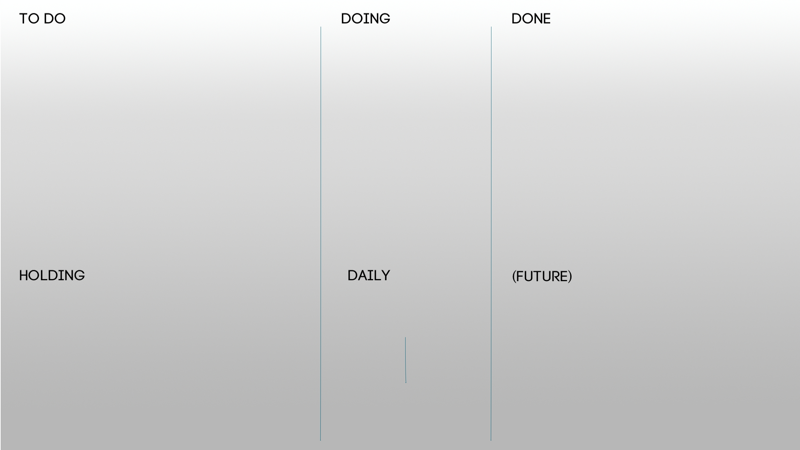

Let’s take a look at this for a moment and see how I modified the three-phase model for my own workflow.

Across the top are the three standard columns: To Do, Doing, and Done.

Across the bottom are the modifications I made to the kanban to fit my workflow: Holding, Daily, and Future.

Holding is where I’d put the tasks in the Doing column that I couldn’t work on until someone else did their thing, e.g., budget figures or travel plans or something they had to get done before I could finish the task.

In the Daily section, I put things like blogging that I did on a daily basis, stuff that it didn’t make sense to keep creating in To Do and then move across the screen every single day. Notice the small vertical line: the Daily section was like a mini-kanban loop inside the Doing column. I could move my blogging sticky from one side of the line to the other to check it off—then move it back.

The Future area was stuff I knew I needed or wanted to work on—just not right now.

Your mileage may vary. It should vary.

Note that kanban is not a to-do list. I still have my to-do’s on my phone: mow the lawn, do the laundry, prep the labyrinth. My kanban is for MAKING THE THING THAT IS NOT and keeping my TASK AVOIDANCE on track.

XXX… <— some kind of conclusion

(Each of the chapters on the Nine Precepts ends with a SO… summary.)

Task Avoidance- SO…

- Use “structured procrastination” by alternating your projects—avoid working on one project by tinkering with another.

- Kanban[2] your projects—know what you’re putting off and why.

- Don’t be afraid to let projects simmer.

- Don’t grind your gears: give yourself some slack.

—————

[1] see RITUAL

[2] Start with http://personalkanban.com

Likewise, there is no shortage of books which will help you deal with your tendency to procrastinate. Why, just yesterday I was contacted by a writer who is writing his own meditation on the subject and who felt compelled to get in touch with the Chair of the Lichtenbergian Society in order to find out more about us—just as I was editing the chapter on TASK AVOIDANCE.

Likewise, there is no shortage of books which will help you deal with your tendency to procrastinate. Why, just yesterday I was contacted by a writer who is writing his own meditation on the subject and who felt compelled to get in touch with the Chair of the Lichtenbergian Society in order to find out more about us—just as I was editing the chapter on TASK AVOIDANCE.