I highly recommend, if you are interested in the inner workings of ritual, Beginnings in ritual studies, by Ronald L. Grimes. It’s introductory, nicely analytical, and clearly written, unlike that other pillar of ritual studies, The ritual process, by Victor W. Turner. Also useful and readable is Liberating rites, by Tom F. Driver. (This is how we know I will never write a book on ritual: I don’t have a middle initial, since Dale is my middle name.) I have not read Ritual theory, ritual practice, by Catherine Bell; every time I look at it on Amazon, it seems thickly written and more about ritual studies than ritual. Perhaps later.

Finally, I found Theater in a crowded fire: ritual and spirituality at Burning Man, by Lee Gilmore, an excellent book for anyone who intends to create a ritual to take into a desert and share with 68,000 hippie freaks for a week.

Ronald Grimes, in chapter 2 of Beginnings, outlines a “map” of ritual elements for the use of those who study ritual in the field. He warns that the map is not a checklist but an overall guide, and that if used carefully can provoke more questions (and questions about the questions), which can then lead the observer to a deeper understanding of the ritual being observed.

So what would an observer make of our ritual?

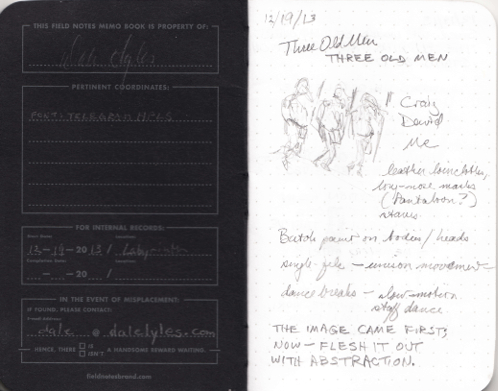

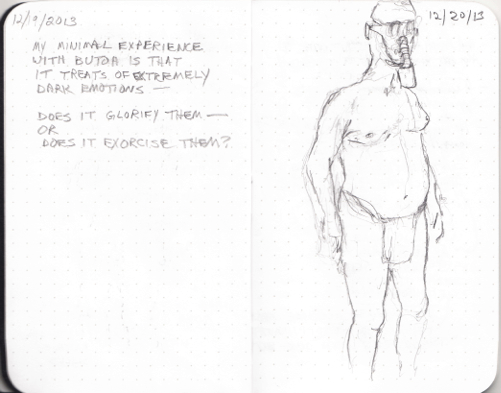

I am going to pause a moment and remind everyone that this little essay is completely theoretical, since at the moment the 3 Old Men is nothing more than scribblings in a couple of notebooks. What will happen when we’re actually on the Playa is anyone’s guess—we will revisit Grimes’s map in September.

Here are some pertinent questions (out of scores Grimes actually posits), and some tentative answers.

: Ritual space :

Where does the ritual enactment occur? If the place is constructed , what resources were expended to build it? Who designed it? What traditions or guidelines, both practical and symbolic, were followed in building it? … What rites were performed to consecrate or deconsecrate it? …. If portable, what determines where [the space will next be deployed]? … Are participants territorial or possessive of the space? … Is ownership invested in individuals, the group, or a divine being? Are there fictional, dramatic, or mythic spaces within the physical space? [Grimes, p. 20-22]

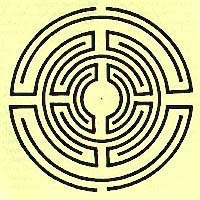

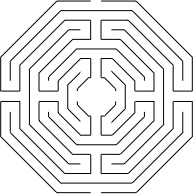

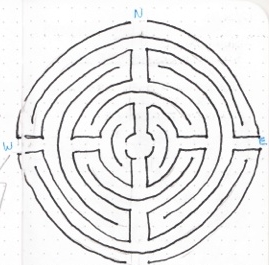

We’re dealing with three simultaneous ritual spaces, of course: Black Rock Desert, Burning Man Festival, and the labyrinth, one natural, the others constructed. Within the Great Ritual of the Burning Man Festival, to which the 3 Old Men are themselves pilgrims, there are hundreds of smaller, dependent rituals, all of which—if divorced from the Great Ritual—risk being seen as purely artificial entertainment, carnival rides if you will. But as Theater in a crowded fire makes clear, Burning Man provides a ritualistic structure that empowers its participants to invest all the smaller rituals with true meaning. The labyrinth derives its potential significance from the Great Ritual.

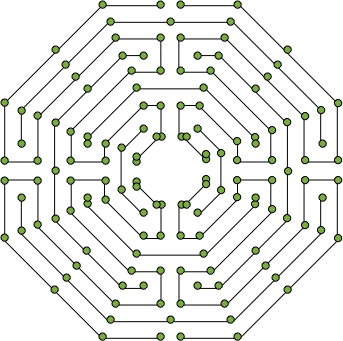

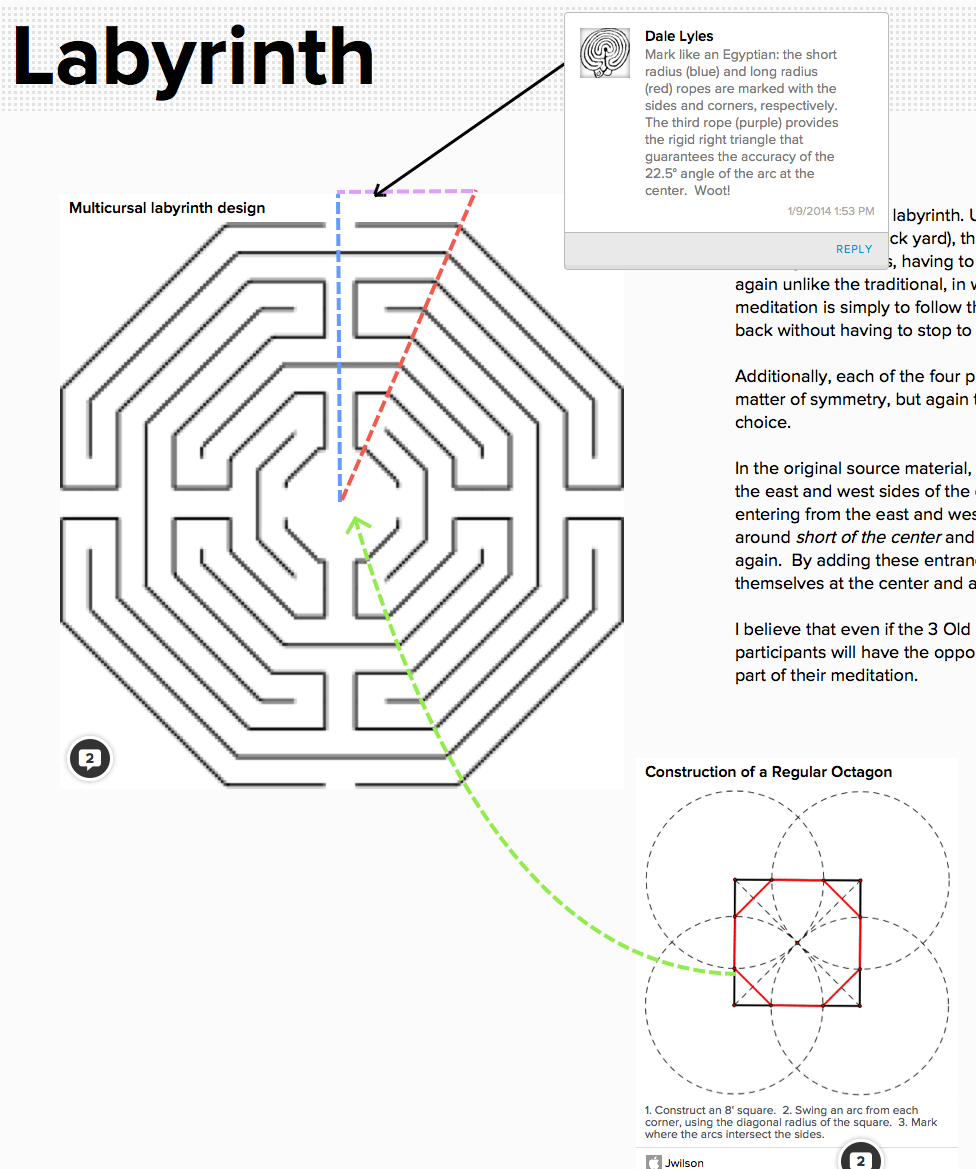

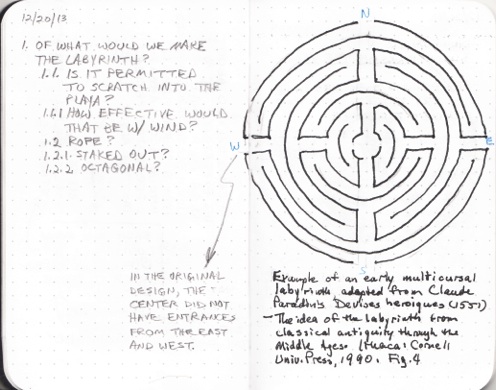

I explicate this theory because the answers to most of the above questions reveal an artificial construct: I and my buddies built it; I designed it; guidelines came from my own study of labyrinths and the Festival’s 10 Principles, which of course are part of the Great Ritual. Again, we can revisit these questions after the Festival and see if there was more meaning to the process than we might think at the moment.

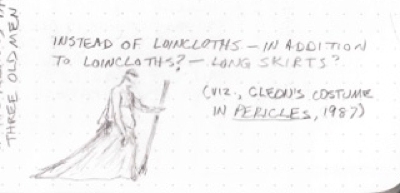

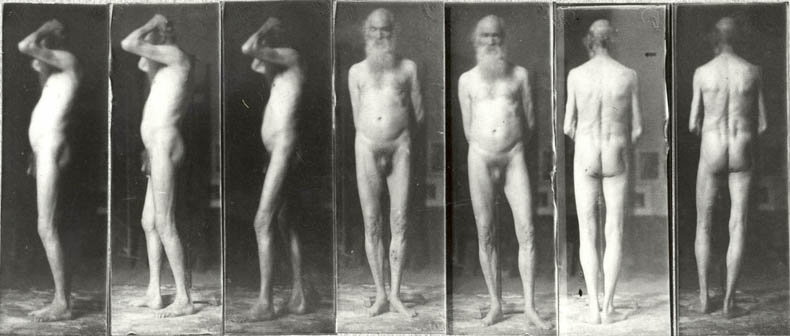

There are a couple of questions which I have not addressed in previous posts that we should look at. Are we possessive of the space? In our discussions so far, the answer would have to be ‘no.’ We’re not concerned with how participants might approach our offering. They may be partying fools or they may be earnest meditators—we will accept what comes. What rites will we perform to ‘consecrate’ the space? Still playing with ideas, but my favorite so far is that we begin in mufti, place our skirts and staffs at our entrances, return to the empty entrance, strip and paint ourselves, proceed through the labyrinth to our posts, don our skirts and take up our staffs, and we’re ready for business.

Who ‘owns’ the ritual space? My hope—probably one of the reasons I’m doing this—is that the group will own it. 3 Old Men, whoever and however many there may eventually be, become actual officiants, caretakers, of this experience.

As for “where next” the 3 Old Men might set up, it has already occurred to us that we can do the whole Regional Burn circuit, can’t we? That’s the advantage of being a dirty hippie freak.

Already I can tell this examination is going to take multiple posts. Tomorrow: ritual objects and ritual time.

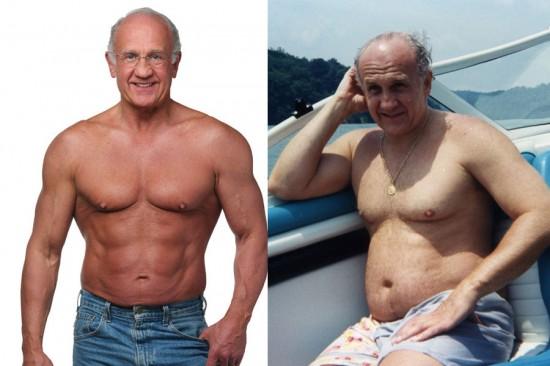

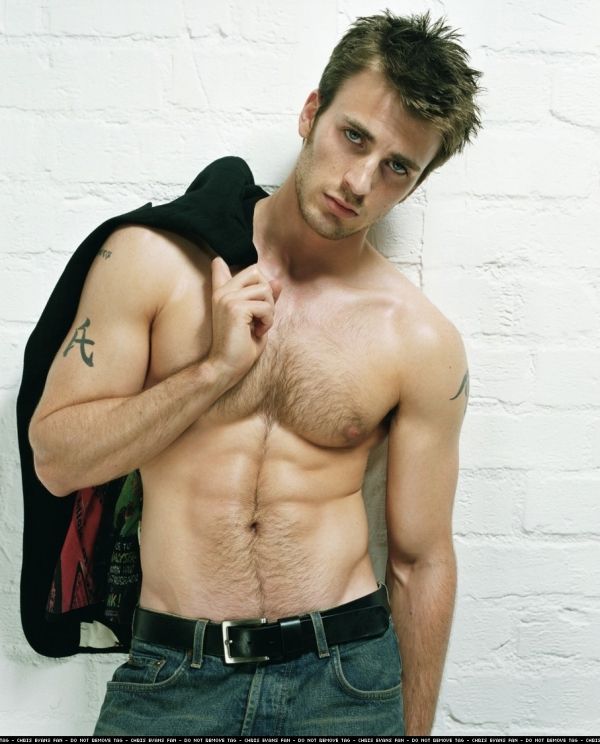

… becomes …

… becomes …